Technical due diligence for the mining industry

The primary purpose of due diligence is to determine the most likely business case and to identify and understand the risks and opportunities which surround that case. This provides a view to assist management to make an informed business decision in accordance with corporate objectives and demonstrate they have exercised due diligence in the performance of their duties. Technical due diligence within the mining industry seeks to identify and understand project technical risks and opportunities in conjunction with legal, commercial and financial due diligence.

Definition of technical due diligence

Technical due diligence is the review by independent experts of the geological, mining, metallurgical and environmental technical parameters of an asset for investment, merger or acquisition purposes. Its results will clearly, concisely and effectively define the relevant technical risks of the asset whilst providing a realistic basis for a range of financial valuations.

Confidence from technical due diligence is the result of in-depth research, with appropriate confidentiality and a clear understanding of the expected returns on investment with reference to risk. The process works systematically through the fundamentals of the technical parameters to determine the areas of technical risk and their likelihood. For more mature assets, material risk to any financial valuation is considered in the likely production profile, therefore, relating technical risk directly to risk of investment and the possible ranges of returns on investment. Exploration prospects are treated somewhat differently in the approach of due diligence, focussing on exploration potential rather than likely production. Exploration potential valuation is a subjective exercise, but this does not remove the need for independent technical assessment; rather it increases the demand for specialist advice.

Every exploration prospect and mining asset is unique in its origin and therefore has unique technical risks. The independent specialist must report these unique technical risks and any impact on production or planned diversion from the technical fundamentals needed to mitigate these risks.

Once a clear understanding of the technical risks has been established, a range of financial valuations can proceed. It is not uncommon that a technical valuation is reported within the due diligence framework but is not essential. Very often, a full due diligence framework incorporates legal, financial and technical aspects and the financial valuations at Fair Market Value are done by the financial team on supply of the production profiles from the technical specialist. This then aids in developing negotiating strategy and pricing of the deal (Rosenbloom, 2002).

Commonly, there are limitations to the due diligence process that shortens the scope and timing of reporting. Initially an investor looks for a technical review due to the time constrained decision on investment criteria, with little understanding of the time required to properly define the technical risks of the project. A technical review is only a brief or initial review of technical parameters to provide an early-stage and general assessment (McCarthy, 2005). Unfortunately, technical reviews are often substituted for a full technical due diligence and expose the investor to higher levels of risk.

Conversely, there are times when the information available is insufficient to fully define the risks and the required production profiles for scenario valuation analysis. This is often the case with projects that have not met the reporting standards, such as the JORC Code or National Instrument 43-101, or are in earlystage development. These require an extended technical due diligence report that provides an independent re-working of certain project components from base data, where those components are investigated and found to be deficient (McCarthy 2005). The advantage of this process is that since independent specialists must comply with these reporting standards, data, models and reports are then produced that meet the required reporting standards. Other requests are also accommodated and may include a review of the financial models to provide an independent opinion on possible financial outcomes, total mine redesign and production forecasting, or alternative mining method investigation.

Regardless of the origin or the unique technical risks of the prospect or asset, the technical due diligence process is sufficient to support investment decisions when carried out independently, expertly and comprehensively.

Within Australian corporate law there are specific definitions of parties providing advice in mining asset transactions and the type of advice provided. Whilst a technical due diligence and technical specialists report may appear to be very similar in standard and scope, they are substantially different in purpose. A Technical Specialists Report (TSR) is commissioned, in most cases, by the Independent Expert providing a public valuation report as defined by the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC). These Technical due diligence for the mining industry Specialists Reports are compiled in accordance with the Code for the Technical Assessment and Valuation of Mineral and Petroleum Assets and Securities for Independent Expert Reports (IER) – The VALMIN Code. There are also similar codes of practice for other regions including: the guidelines and ethics of the American Institute of Mineral Appraisers (AIMA) in conjunction with The Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP) and the CIMVal Code in Canada; and in South Africa, the Code for the Reporting of Mineral Asset Valuation – The SAMVAL Code.

A technical due diligence is most commonly an internal process meant to sufficiently inform the directors or management of a company acquiring or investing in a target company or asset. It may become a public document through disclosure in full or in part to stakeholders on the permission of the reporting entity. This is why it is often necessary to also approach a due diligence from a VALMIN compliance prospective.

Both due diligence reports and technical specialist’s reports are based on what provides a fair and reasonable technical basis for valuation. This fairness and reasonableness underpins the IER opinion on Fair Market Value, which is an estimate of what the acquirer would pay the target company in a free market for the asset in question. Due diligence provides only the technical parameters used to value an asset, with the valuation usually completed by the acquirer internally. It is not uncommon that a sound technical due diligence often provides the basis of a TSR intended for public release, although this is more the exception. In some instances there is a request from the acquirer to extend the due diligence to include a technical valuation.

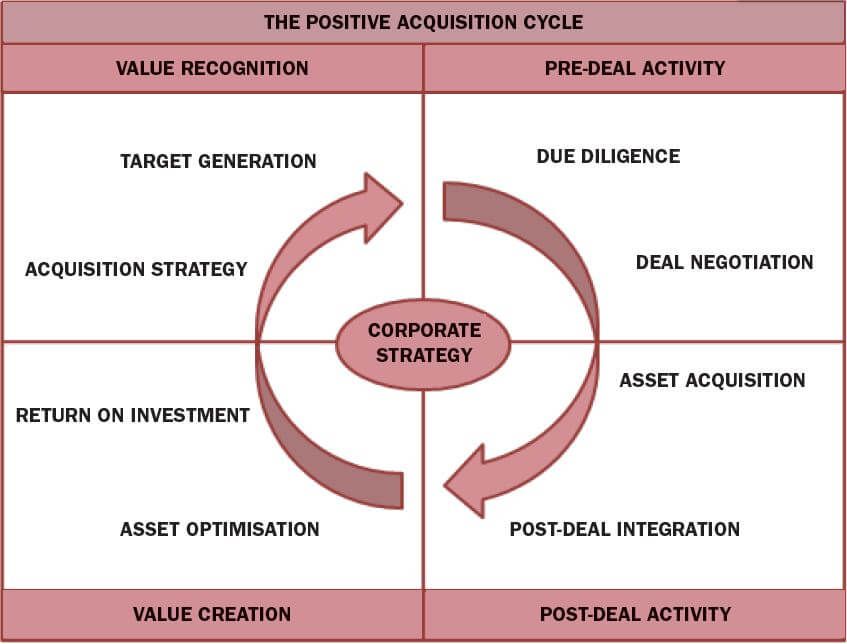

Building a business case through technical due diligence

Appleyard et al (2001) stated “the right Ore Reserve is the one that best achieves its owner’s objectives.” It is true also of the technical due diligence process. Any technical due diligence should always consider the view point of the acquirer and their needs in terms of integrating the technical outputs into their financial, legal and other due diligence processes whilst being relevant to the acquisition strategy. This is particularly so with assessing project risk. Where one acquirer may see the life of mine and associated risks, such as limited exploration upside, as important, another may be concerned with short term finance payback and immediate production risk.

Normally the acquisition strategy is to maximize the economic return, which may be measured by the Internal Rate of Return or by the Net Present Value at a selected discount rate or by some other technique. However, there are alternative strategies that may be based around maximizing the production rate of the commodity to improve share market rating, maximizing the life of the operation to give the associated exploration effort the best chance of extending the project economically, or getting most of the value in the early years in a location considered to have political or other risk (Appleyard et al, 2001).

In essence, it is much like buying a car. If you are a salesman looking for a reliable car for travelling long distances, the car’s dependability and comfort may be of most importance. Therefore, looking at a car only suitable for short distances to travel from home to the shops would be a mistake. The reason or strategy behind your purchase is very important to determine the most suitable car for you. Calling on a mechanic, the technical specialist, to assess the car prior to purchase is a good way of reducing the risk that you will end up with a car not suitable to your needs.

When engaged early in the process, the technical specialist can add tremendous value throughout the proposed investment, merger or acquisition timeframe. If possible, the technical expertise should be applied at the strategy formation and target screening phases to help determine the best outcome for the investor. An early engagement also facilitates a more constructive due diligence, with more appropriate site visit timing, that would address project risk more comprehensively.

Post-transaction, the same technical expertise can be called upon to optimize the investment and facilitate integration, improving return to stakeholders. Rosenbloom (2002) stated “Operational due diligence should provide the intelligence needed to develop the post deal integration plan. Experience has shown that a merger is more likely to succeed having a detailed integration plan in place and ready for execution”. This is particularly important for alignment of the acquirer’s strategy with the mine plan. What was once an optimal mine plan pre-deal, becomes a sub-optimal mine plan post-deal as the strategy and required return to shareholders dynamic has changed. Commonly, mine plans are not reviewed post-deal, in the context of the new investor’s strategy. Hall (2006) stated “optimal plans have been found in many cases to be relatively insensitive to changes in major value drivers, such as metal prices, while suboptimal strategies are frequently found to have a significantly greater financial risk. Identifying and then operating within the framework of an optimal strategic plan can have substantial benefits over a plan being continually driven by short-term tactical issues.” Therefore, post-deal technical support is as important as the due diligence process in its ability to leverage the best outcome for the investor.

Often the due diligence process has started before the technical specialist has been engaged. A strategy has been formed and target screening has commenced. Financial and legal processes have been initiated and preliminary negotiations have begun. The time left for a technical due diligence is minimal as parties have agreed to a timetable without regard to the technical risks. What can the acquirer do to help the technical specialist complete their due diligence in the time remaining?

- Clearly communicate the strategy behind the proposed investment, merger or acquisition;

- Provide the required inputs and the format of the inputs for financial analysis;

- Provide a contact within the acquirer’s team that can answer questions and discuss project management related issues directly and in a timely manner; and

- Co-ordinate interaction with the target’s owner and/or manager.

The technical due diligence framework

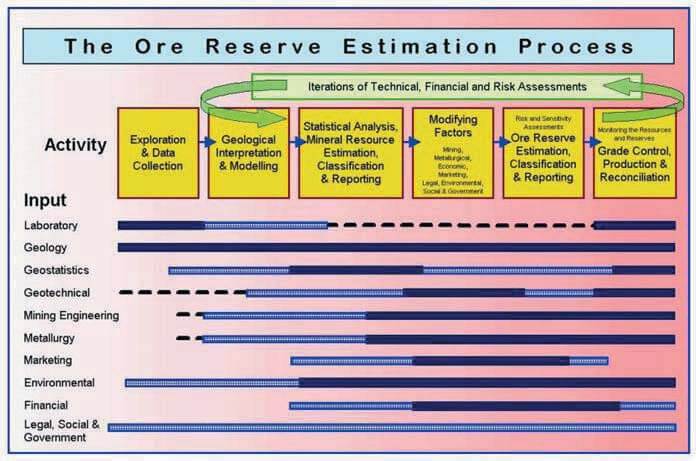

The process for ore reserve estimation as summarised by Appleyard et al, 2001, defines the context for the key questions within the technical due diligence process. These are questions that pertain to the inputs and the activities in deriving the resource and reserves on which an assets value is determined.

Based on Rosenbloom’s (2002) generic framework for operational due diligence, the technical due diligence team when reviewing the inputs and activities of the ore reserve estimation process should consider:

- The deal rationale;

- What concrete goals are expected?

- A plan for achieving those goals;

- The drivers of value creation and any significant hurdles;

- The critical aspects and fatal flaws;

- Post-deal integration requirements;

- The negotiation and pricing strategy;

- The macro framework, e.g. trade growth;

- The economic factors e.g. foreign exchange rate; and

- Political factors including social obligations.

Within this framework, the technical specialist should seek to answer the following key questions:

- Does the physical property (reserves, buildings, equipment, etc) really exist?

- Can the physical facilities operate and perform as proposed?

- Does the owner have the rights and permits to mine, process, and sell the commodity?

- Is the proposed concept reasonable and achievable?

- Is the proposed capital reasonable and adequate to achieve the project objectives?

- Are the proposed operating costs reasonable and adequate to achieve the project objectives?

- Is the proposed schedule reasonable and achievable?

- Is the proposed sales forecast reasonable and achievable?

- Are there any errors, omissions, or duplications?

- What outstanding current or future liabilities exist?

- Are there any other factors that will negatively or positively affect the project?

The process develops answers to these key questions by completing:

- Visits to data room / target’s office;

- Reviews of documents, reports and public information;

- Mine/Plant/Warehouse/Terminal site inspections;

- Inquiries with regulatory agencies (ie tenement title);

- Audits of geological resource and reserve inputs, modifying factors, grade control and reconciliation;

- Discussions and validation of contracts with suppliers and contractors; and

- Discussions with target entity staff.

In answering the key questions, Santini et al (2006) stated that a formal technical due diligence report when presented should include the following:

- Proof that the asset exists as represented by the target entity that has the right (title) to sell it. Commonly title verification is undertaken separately by an appropriate title specialist or lawyer;

- Identification, description and assessment of assets and associated risks;

- Discussion of strengths and weaknesses of the operation; and

- Determination of technical value.

To answer key questions certain information is required by the technical due diligence team, to the extent that it is applicable:

- Organizational structure, brief resumes of existing managers and recruitment strategies to fill key vacancies;

- The last six monthly management reports for operations and the reports for the last month of the two previous years (containing the year-to-date data for the previous 12 months);

- Reports on mineral resource and ore reserve estimates (and any external reviews);

- Details of inputs to ore reserve estimates including costs, geotechnical constraints, metal prices, exchange rates and philosophy in relation to such estimates;

- Detailed statements of mineral resource and ore reserve estimates, including stockpiles;

- Description of and reports on the grade control system, including stockpile management;

- Ore reserve to mill reconciliation reports (and any external reviews);

- Life-of-mine plans including production and cost schedules and supporting information, including stope, pit and development design strings;

- Current year budget documents, budgets for the coming year and three or five year plans or similar;

- Recent and current geotechnical assessments for the mine, tailings dams and waste dumps and, if relevant, infrastructure;

- Description of and reports on concentrate handling and transport systems;

- Current exploration programs and review of near mine exploration drilling and targets;

- Studies, development plans and strategy documents for projects;

- Metallurgical test work results and reports including projected recovery rates, work indices, reagent, water and power consumptions, treatment costs versus current and historical performance, having regard to expected changes in ore types, etc;

- Processing plant and infrastructure condition reports;

- Mining equipment lists, including age and condition reports;

- Details of significant contracts, claims and matters likely to give rise to a claim;

- Discussions or analyses of opportunities and threats; and

- Reports on external reviews of the above.

As referred to in the list above, the specialist will require the target to provide its life-of-mine (‘LOM’) production and cost schedules for each operation or project.

In addition to the general information listed above, the specialist will also require the following (including drafts of any documents currently in preparation) in relation to the environmental aspects of the operations and projects:

- Closure plan, progressive rehabilitation costs and estimated closure costs and post-closure monitoring reports (as applicable);

- Quantitative details of areas cleared and disturbed, by activity type (e.g. waste dump, plant-site, pipeline, tracks/roads, etc) – summary table and drawing/aerial photo highly desirable;

- Unit rates used in estimating closure costs;

- Details of any rehabilitation/ environmental bond(s);

- Most recent sustainability report or public environmental report;

- Most recent internal (to management) environmental annual report, four most recent quarterly environmental reports and/or 12 most recent monthly environmental reports;

- Any internal or external environmental audit or review reports (including government site inspection reports);

- Most recent environmental annual report to government/agencies (last three years if possible);

- Details of any environmental violations or non-compliance with lease, permit and/or license conditions or applicable government regulations with copies of all conditions of environmental approval, licenses and permits – including tenement conditions;

- Current Environmental Management Plan;

- List of environmental commitments/ obligations;

- Environmental leases, permits and licenses, including indigenous approvals (and a summary of the status thereof) and a renewal schedule;

- Details of any outstanding environmental issues/actions;

- Environmental Impact Assessment and its approval conditions (plus supplements to the EIA if any were prepared).

- Details of indigenous and community relation issues;

- Map showing nearby properties (other than those owned by the target entity) and locations of nearby residences;

- Corporate environmental requirements that apply to the sites; and

- Any other relevant environmental or socio-economic documentation.

Site visit

No due diligence can be completed without meeting the minimum requirement of a site visit. McCarthy (2006) stated:

“The specialist needs to prepare a succinct but adequate picture of the operation as it currently stands. To do that the specialist needs to develop a good understanding … of the operation and to assess past performance … issues which are material to achieving projected performance … the orebody … any plans for change of production rate or any constraints to projected production rate … and upsides to existing reserves. To achieve this, the technical specialist needs to physically see material aspects of the operation and its assets and to meet the managers to sign off on management status and practices.”

The technical due diligence team will usually comprise a geologist, mining engineer, metallurgist and environmental specialist. The team may also include other specialists if specific issues are foreseen such as geotechnical or social issues. The team would normally expect to be on site for at least two to three days.

Technical risk and its implications

A large part of the technical due diligence process is determining risk. Risk, the product of probability and con sequence, is an integral part of mining. Whether evaluating exploration priorities, determining property acquisition potential, reviewing the components of an operating mine or assessing environmental closure issues, the concept of minimising risk is central to economic and technically appropriate decision making (Davies 1997).

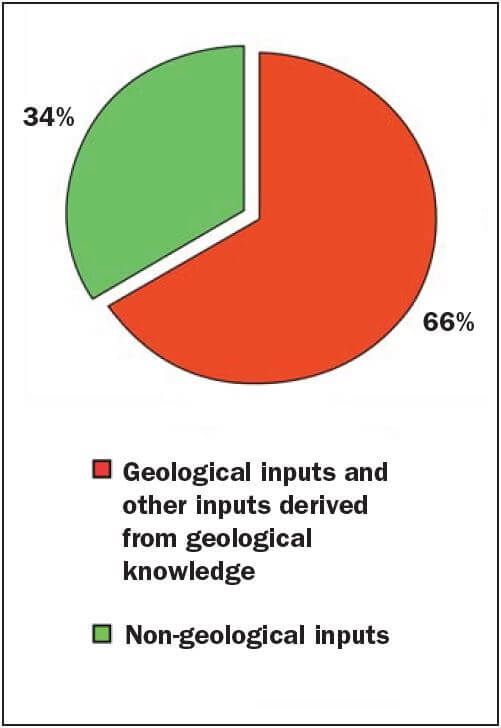

Some research has been completed (Berry and McCarthy, 2006) that outlines the technical areas that form a source of risk in mining operations. Two thirds of these risks can be attributed to geologically-based risk.

According to Berry (2007) the failure to recognise and mitigate these risks may lead in extreme examples to premature mine closure resulting in substantial asset write-down and destroyed shareholder value. In most cases mines will not operate as profitably as expected, reducing shareholder value through:

Unplanned capital costs, and/or;

Higher operating costs, and/or;

Lower revenues, and/or; and

Occupational Health and Safety incidents.

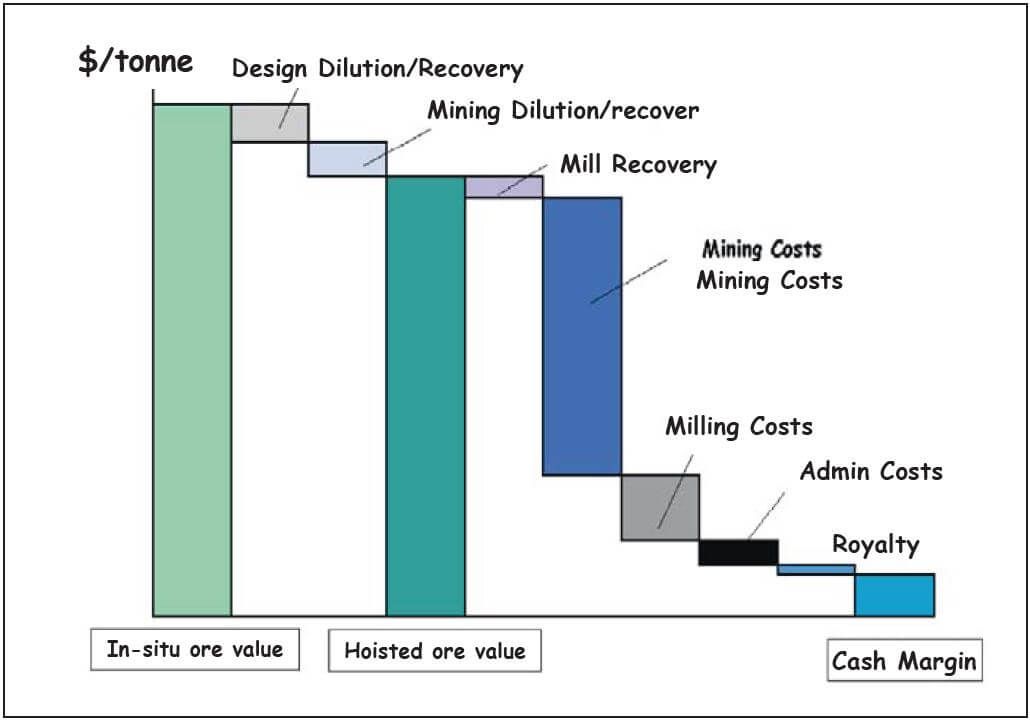

To further illustrate the need for technical due diligence the various technical influences on cash margin are shown in Figure 4. These influences are compounded when considering the sources of technical risk associated with ore reserve estimation in the ‘in situ ore value’.

FIG 3 – Geological verses non-geological sources of risk in mine feasibility studies (Berry and McCarthy, 2006).

An example of the serious impact from inadequate reserve estimation is the well published Shell – Oil Reserve write downs. The Royal Dutch Petroleum Company and The Shell Transport and Trading Company announced a re-categorization of 4.47 billion barrels of oil equivalent (‘boe’), or approximately 23 per cent of its proved reserves as reported at the end of 2002. These reserves did not comply with the definition of Proved Reserves in the SEC rules (see SEC Administrative proceedings File 3-11595). These re-categorizations included reserves at Gorgon, northwest shelf, Australia, Nigeria and Oman. The companies agreed, among other things, to pay a US$ 120 M civil penalty as a result of court action by the USA SEC.

The United Kingdom Financial Services Authority (FSA, 2004) also took action against Shell and imposed a financial penalty of £17 M on Shell for breach of the FSA’s Listing Rules. Shell’s overstatement of Proved Reserves resulted from a number of breaches of the separate provisions of the definitions of Proved Reserves, and the penalties were influenced by the failure to act when these failings were initially flagged internally, but also by the co-operation of Shell with both the SEC and the FSA. Note that Shell announced the write downs prior to action by the authorities. While the case quoted is a major example which made headline news, there are numerous non-public examples of the adverse consequences of poor resource/reserve estimates, including major cost blow-outs, incorrect mining method/equipment decisions, incorrect metallurgical design decisions, incorrect financial statements, under or over valuation of the project or company, failure to meet loan conditions, and failure to meet market specifications, or incurring of penalties.

Conclusion

Technical due diligence is an important part of the positive asset acquisition cycle. A review by independent experts of the geological, mining, metallurgical and environmental technical parameters of an asset is critical to understanding the technical risks whilst providing an expectation of returns on investment. However, it is best left to Agricola to summarise the principle of sound technical due diligence:

“The miner ignorant and unskilled in the art digs out the ore without careful discrimination while the learned and experienced miner first assays and proves it, and when he finds the veins either too narrow and hard or too wide and soft, he infers therefore that these cannot be mined profitably and so works only the approved ones.” (Agricola, 1556).

Tim McManus, MAusIMM (CP)

This article first appeared in the 5 October 2010 edition of the AusIMM Bulletin.

Acknowledgements and references

Agricola, G, 1556. De Re Metallica (Translated by H C Hoover and L H Hoover) (Dover Publications: New York).

Appleyard, G R, Gilfillan, J F andNorthcote, G, 2001. Mineral Resource and Ore Reserve Estimation – An Overview and Outline, Mineral

Resource and Ore Reserve Estimation – The AusIMM Guide to Good Practice (ed: A C Edwards), (The Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Melbourne).

Australian Securities and Investments Commission, 2005. Consultation Paper 62; Better experts’ reports [online]. Available from: <http://www. asic.gov.au>

Australian Securities and Investments Commission, 2007. Regulatory Guide 111; Content of expert reports [online]. Available from: <http://www. asic.gov.au>

Australian Securities and Investments Commission, 2007. Independence of experts [online]. Available from: <http://www.asic.gov.au>

Berry M, 2007. Understanding and Conveying Geological Uncertainty in Mining. Berry, M and McCarthy, P, 2006. Practical consequences of geological uncertainty, in Proceedings 6th International Mining Geology Conferencepp 253-258 (The Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Melbourne).

Davies, M R, 1997. A Potential problem analyses: A practical risk assessment technique for the mining industry, Klohn-Crippen Consultants Ltd, Richmond, British Columbia. Deloittes 2008. Merger & Acquisition Library — Due Diligence [online]. Available from: http://www.deloitte. com /dtt/article/0,1002,sid=109077 &cid=161535,00.html

Financial Services Authority, The (FSA), 2004., Final notice, The ‘Shell’ Transport and Trading Company pl.c, 24 August 2004.

Gillett, L, 2005. General information required by a technical due diligence team, AMC Consultants Pty Ltd.

Hall B E, 2006. Short term gain for long term pain – How focusing on tactical issues can destroy long term value, 2nd International Seminar on Strategic versus Tactical Approaches in Mining, 8-10 March, Perth, WA.

Horsley, initial? and Medhurst, initial, 2000. Quantifying geotechnical risk in the mine planning process, in Proceedings MassMin 2000, (The Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Melbourne).

JORC, 2004. Australasian Code for Reporting of Exploration Results, Mineral Resources and Ore Reserves (The JORC Code) [online]. Available from: <http://www.jorc.org> (The Joint Ore Reserves Committee of The Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, Australian Institute of Geoscientists and Minerals Council of Australia).

McCarthy, P J, 2005. AMC definitions and guidelines for varying levels of independent technical review and due diligence, AMC Consultants Pty Ltd. McCathy, PJ, 2006. Technical due diligence site visit objectives, AMC Consultants Pty. Ltd.

Rosenbloom, AH, 2002. Due Diligence for Global Deal Making (Bloomberg Press: New York).

Santini, K et al 2006. Due Diligence and Financial Valuation of Industrial Mineral Assets, Industrial Minerals and Rocks; Commodities, Markets and Uses seventh edition, (Society for Mining, Metallurgy and Exploration Inc: Littleton).

SEC, 2004. Administrative Proceedings File 3-11595 Royal Dutch Petroleum Company and The ’Shell’ Transport and Trading Co. plc., 24 August.

Subscribe for the latest news & events

Contact Details

Useful Links

News & Insights