How to rein in your mining costs and improve margins – Part 2

Cost reduction is important right now, but sometimes the operating margin can be improved by spending a little more in selected areas. Many senior executives acknowledge that while chasing throughput was the priority goal during the boom, they lost control of productivity and costs. Now they may be left with a systemic operating cost and productivity problem, a demoralized workforce and a management team reeling in the aftermath of severe across-the-board cuts. This isn’t the first time the industry has been at this stage of the cycle. Learning from previous experience can ease some of the burden and provide opportunities to improve. In this second of a two-part series, AMC’s senior consultants provide some ideas on how to rein in mining costs and improve margins.

Mine planning

Planners should be held to account for sloppy design and sloppy practices, but it seems the same issues occur over and over. Bad designs are reiterated, poor decisions made. Implementation of well thought out and approved plans can also suffer as production focuses on short-term cost reduction. Often production supervisors are rewarded for such practices but they can lead to medium-term, or even relatively short-term losses, through rework or oversight. The production department is often guilty of taking short-term options and not sticking to schedules. Too often a quick decision to change from the schedule leads to longer-term problems by sterilizing areas and undermining ground support planning. It also is an obvious cause of poor reconciliation against budgeted/forecast positions. Putting operations under pressure ‘to move dirt faster’ leads to decisions like temporary stockpiling therefore leading to double handling, loss of control of ore type and bad accounting of material movement. Mine planning and mill planning need to talk to each other on a regular basis for stockpiling strategies and changes to mill feed.

Staffing

Start with head office administration. Some companies are run like government departments, but they still nit-pick over the number of field staff onsite.

Technical staff add value, they are not cost centres. Too many mines run understaffed and fail to optimize their operations. Keep adding geologists and engineers until you reach a marginal break even benefit. Too many mines are running their technical people at break neck speed. Computerized systems can be used effectively but often become unwieldy and misunderstood because true knowledge of the system has walked out the door when people leave. If a computer system stops for any reason there should be no reason why, given time, people don’t know how to work out production figures. If they are flummoxed, they don’t truly understand what they are reporting. Rebuilding these capabilities is not just a case of rehiring. The experience and knowledge base acquired by a long-term planning team is often not recognized even though it is a key part of the operation’s ability to improve productivity, margin and profitability.

Cost reporting

Avoid allocating costs needlessly. Mines must have a general mine services or a shared mine service cost centre. The costs that accountants attempt to allocate are often a function of running the whole mine and are not attributable to an individual activity. Engineers and managers, in concert with accountants, should take the time to set up the cost structure so that they can use it to forecast and manage costs. Graphical communication of costs showing trends and relativity are far more effective than tables and numbers.

Having separate budgets for capital and operating costs can be misleading. Capital costs should be tracked separately for reporting purposes but they should all be in the one budget to enable the all-in cost of operations to be determined. Changing the cost structure year on year makes life very difficult for the operators. A well thought through and life-of-mine cost structure established at the beginning of a project is worth every bit of the effort.

Setting KPIs Simple cost KPIs that drive the total cost for a cost centre should be developed. You don’t need to produce every possible graph that you can think of because it looks good in a monthly report. Graphing must be meaningful. Reporting productivity and costs KPIs to the relevant people and then focussing effort on these numbers will help to improve the ownership by the workforce and their feeling that they can “make a difference”.

Poorly chosen KPIs can result in practices that are detrimental to the overall operation. Practices that may have worked at one mine may not necessarily be optimal for another. Mining professionals change jobs relatively frequently and it is only natural to implement ideas learnt from experience. However, they are not always transferable. Ensure KPIs drive the correct behaviour for the long term with KPI’s timeframes reflective of the role in the operation. It isn’t all about costs

Sometimes operating margins can be improved by spending more. Unit costs per tonne rise, but the product quality rises faster. Cut-off grade studies show where the value lies. Apply benchmarking to identify where you are not competitive but don’t just leave it there – apply analysis to see if a material change can be made. Act on it if it is material. Apply a sensible cut-off that maximizes company value – not some senior manager’s or executive’s KPI. Conduct “Hill of Value” studies to assess the right size for your operation. You may not have the ability to change this (locked in by a hungry process plant for example) but it may provide ideas on how to adapt. Seek independent advice from experienced and seasoned professionals and/or well-established consultants. Current generation management may not have the required experience and/or skills.

Review all long-standing procedures. Check that the situation or requirement has not changed since it (the procedure) was first established. An example could be ground control standards. Look at things that improve value and not just cut cost. The higher priced “widget” or “service” may ultimately provide far better value. Get employees involved and committed. Get them to advise “what would you do if it were your own business”. They are likely to discuss the issues “on-the-ground” that are not evident from management reports. Stick to what you do best – stay true to the core of your business.

There should be a systematic approach, and improvements should be supported by improved systems so they are sustainable. Start by ensuring the right people are in the right jobs and the role descriptions are well understood. So, get the people right first. Then identify where the leverage points in the operation are. What activities are anomalously costly? What activities have the most potential to improve the bottom line? Install a Business Improvement culture and BI processes in the daily/weekly/regular operating practices – control charts, target setting, measuring, reporting, rewards, incentives etc. Instigate a schedule of mining process reviews to reduce waste in the system, remove duplication, remove rework. Target a maximum of, say, five key improvement projects at any one time and get those right before moving on. Too many improvement targets reduce focus. Measure and report costs against budget and assign accountabilities to individuals – you can’t manage what you don’t measure.

Equipment productivity and utilization All too often in the recent past, delivery of material has been the priority and excess equipment has been mobilized without evaluation of whether more material will actually be moved. Pit constraints and equipment interactions have not been considered in the decision making. As a result, operating and fixed costs have increased because excess equipment is idling or being parked up, leading to poor productivity and poor utilization.

Mining equipment productivity is a key focus area for reducing total mining costs. Sounds simple but it can be hard work and many miss the opportunities. It is simple and it is about increasing the amount of productive hours and increasing the amount of material moved per hour by removing waste and inefficiency. All aspects of productive hours and material movement must be measured and monitored (eyes and ears) if improvement is expected. Everyone has a part to play and all must simply pay attention. The objective has to be maximizing equipment availability (within constraints) and maximizing the productive use of equipment availability together.

Some items for consideration:

- Minimize inter and intra-shift delays – shift change, crib, meetings.

- Reduce equipment cycle times – what are the delays and inefficiencies in the digger and truck cycle times?

- Improve bucket/dump body fill factors – improver payloads, poor fragmentation, the closer to rated payload the better.

- Improve operator efficiency.

- Site conditions.

- Haul road design – incline/decline, switchbacks, super-elevation.

- Haul road maintenance.

- Location of service facilities, particularly for trucks.

Mine plan conformance

With less-experienced engineers promoted into senior roles, many do not appreciate the difficulties associated with delivering a plan. Good weekly and monthly reconciliations against plan (meaning not just the tonnes mined, metres developed etc, but whether the right tonnes were mined, right areas developed etc) will identify problem areas so impacts can be assessed and rectified earlier, which means the capacity is being used efficiently, otherwise unnecessary costs will be incurred. More geotechnical ideas

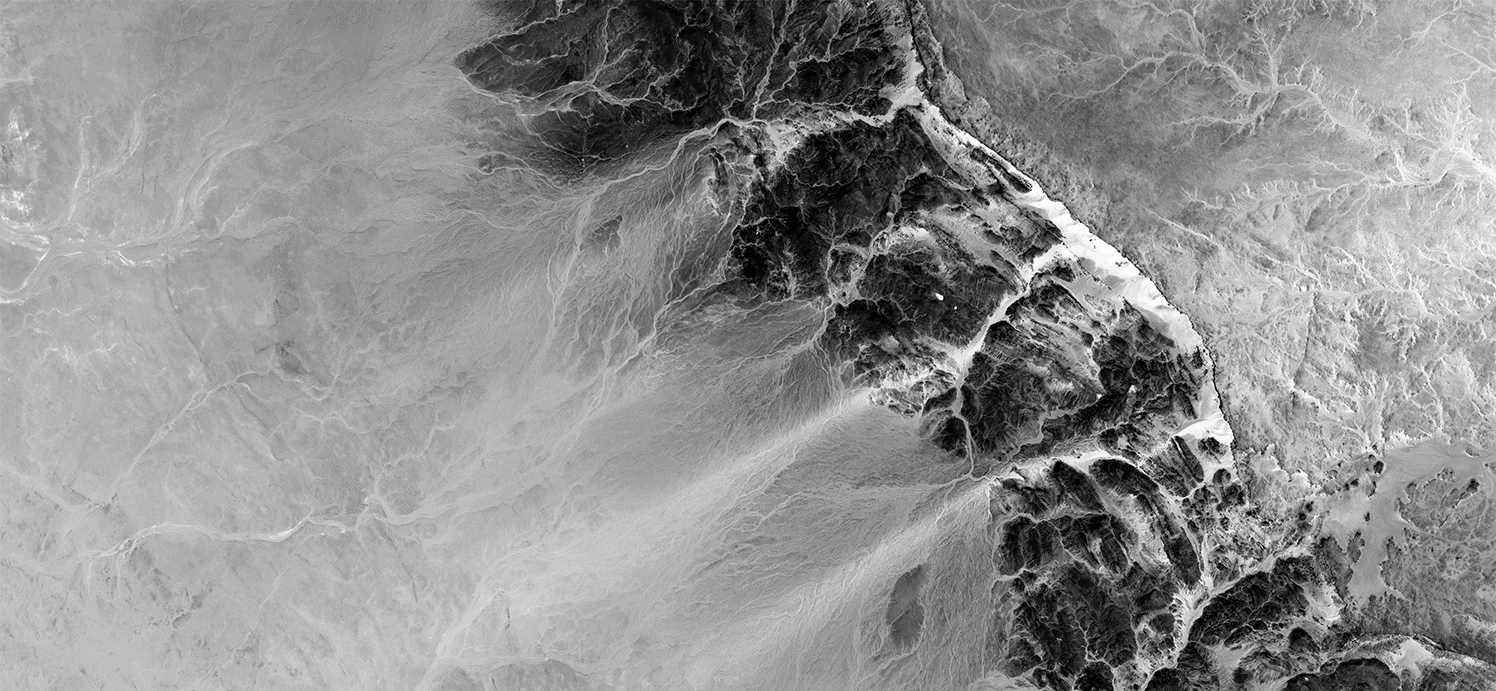

Slope failures can be costly and catastrophic – design, assess, monitor. Cutting the ability of the operation to do these things can lead to major unforeseen costs for little short-term saving. Monitoring also means making sure that in open pits the walls are scaled and cleaned so that they can be mapped safely at the end of the bench. Structures need to be seen so that they can be mapped and monitored over time.

Thanks to … Johann van Wijk, John Sheehan, Kingsley Hortin, Ben Cottrell, Rob Chesher, Joy Hill, Peter Mokos, Bruce Gregory, Damian Peachey, Colm Keogh, Ben Cottrell, Chris Arnold, Mani Rajagopalan, Mark Chesher, Abouzar Vakili, Marcus Scholz, Dean Carville, Rod Webster, and Tony Grice.

To read Part 1 of this article,

click here.

Subscribe for the latest news & events

Contact Details

Useful Links

News & Insights